PATRICIA JOHANSON: ULSAN PARK, KOREA

| Excerpt from: Patricia Johanson: "Preserving Biocultural Diversity in Public Parks." Republished from: NAPtexts(s): A Literary Journal, volume 2, number 2, 1997. The New Arts Program, Kutztown, Pennsylvania, James F.L. Carroll, Director |

|

|

|

ULSAN DRAGON PARK occupies 912 acres in the middle of Korea's leading industrial city, home of Hyundai, shipbuilding, and the largest oil refinery in the world, Yukong, Ltd., the donor of the park. The Korean people traditionally loved and worshipped nature, so the challenge is to combine Korea's agrarian, Shamanistic past with its high-tech industrialized future, while also serving the recreational needs of a million people and creating a sustainable environment. The park program requires many major built structures—a city museum, exhibition complexes, promenade, and Imax Theater—all interwoven with restored natural ecosystems: marsh, pond, intermittent creek, floodplain, meadows, wetland and upland forests. The animals, insects, and plants that live in Ulsan Park will primarily be those seen in Korean folk paintings (Minhwa), creating links between past myths and images and contemporary life forms. Thus the grasshopper seen in the park today is the descendant of the grasshopper painted centuries ago by our ancestors. It becomes clear that Ulsan Park is not just reflecting the cultural history of the past, but also protecting and transmitting genetic information to the future. Many elements in the park function simultaneously as art, cultural symbol, habitat, and utilitarian structure. A "Haitai Bridge", based on a powerful mythical animal, guards the entrance to the promenade. The Haitai's legs and paws interweave vegetation and nesting shelves for birds with overlooks, steps, and seating terraces for people, forming a transition to the wetlands fifteen feet below.  Mountains and remnant floodplain frame the PROMENADE (in construction), with Ulsan City as backdrop. A "Carp Playground" consists of a series of fish-scale terraces that flow from the mountainside down to the floodplain. A rivulet, manually activated by pumps, waterwheels, and sluice gates teaches children about water management as they fill reservoirs and wading pools and build cities of pebbles and sand. At the bottom of the play terraces are narrow paths that lead through wetland planting, vernal pools, and a variety of floodplain microhabitats, such as amphibian breeding grounds. |

|||||

|

||||||

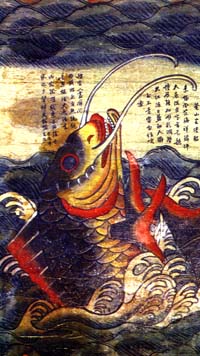

According to legend, every spring old CARP gather under the Dragon Gate and compete to jump the highest. The winning carp transforms into a dragon. At Ulsan Park the Dragon Gate has been designed to provide food and habitat for many different creatures, including birds, bats, butterflies, and insects. |

||||||

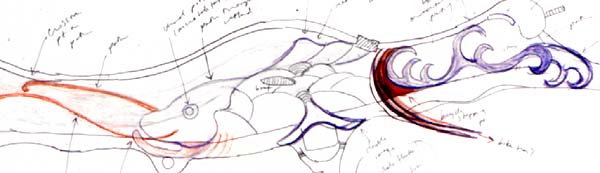

CARP PLAYGROUND - © Patricia Johanson 1996

Located along the Promenade near the northeast entrance to the park, the terraces—which are animated by pumped water, as well as rainwater flowing off the mountain— combine nature and culture. Along the Promenade, whale images relating to Ulsan's past, are overlapped with the Carp's mouth and fin to form special areas. A decommissioned whaling ship in the floodplain below becomes the focal point for local history, climbing, and adventure play, while the lower terraces are inscribed with Ulsan's famous petroglyphs, forming tiny microhabitats as water collects in channels and puddles. Within the floodplain itself, narrow paths (the Carp's whiskers) and a round pool (the Carp's eye) structure educational programs and nature walks. Further east along the Promenade, the Carp transforms into a wave pattern that frames ornamental lotus ponds and fish pools inhabited by living carp. |

||||||

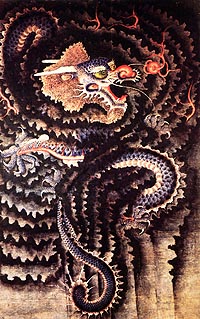

A "Forest Playground" features rope-climbing structures at different elevations—ladders, nets, and webs, with safety nets underneath. Aerial walkways, rope suspension bridges, and tree houses reveal forest stratification, canopy habitats, and bird's eye views of the park. Tigers inhabited the forests of Korea up until the early twentieth century, and they remain a powerful cultural symbol, as protective guardian, folk-tale hero, and image of the "Mountain Spirit". A "Tiger Valley", that people can circulate through in caged walkways, contains real tigers, as well as a Sanshin-Dang (shrine building) housing the message of the Mountain Spirit: that this beloved animal is now extinct in Korea due to deforestation and habitat loss. The educational program at Ulsan Park is centered around such issues as the survival of species, biodiversity, and the sustainable use of water, forests, energy, and agricultural land. To Korean people, the concept of longevity has great significance, therefore gardens devoted to such longevity symbols as turtle, crane, deer, pine, and bamboo are designed to be not only poetic and deeply enmeshed in the cultural psyche, but also create ecosystems where these plants and animals can survive. Perhaps the most powerful symbol in the park is the dragon, an enormous image that appears in fragments throughout the site, uniting wetlands, valleys and mountaintops with the more urban areas of the park. It is now clear that the dragon is more than a myth, most likely an ancient pterosaur such as Quetzalcoatlus, a flying reptile about the size of a small plane, with claws, scales, and bat-like wings. Like the dragon, the pterosaur occupied both watery places, where it fished and hunted crustaceans, and the upper atmosphere where it was an expert at long-endurance soaring. Koreans have always understood the dragon as a mediator between heaven and earth—the Celestial Dragon and the Water Dragon—responsible for rain and agriculture as well as bountiful sea harvests. Contemporary ecological thinking also envisions the flow of energy between water, air, and earth, thus the dragon becomes a metaphor for the elements and processes of nature, its cycles of production, decomposition, and transformation. When water was worshipped in Korea as the sacred sustainer of life, water pollution was not a problem. Perhaps by reintegrating nature and culture within public landscapes, we can ensure the transmission of both ancestral truths and the preservation of the gene pool that ceaselessly provides new forms, meanings and products. |

||||||

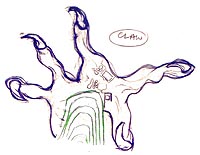

DRAGON CLAW: ROCK AND BAMBOO GARDEN © Patricia Johanson 1996 The "Dragon Trail" — the "spine" of both mountains and "dragon" — consists of a series of "Longevity Gardens" devoted to Turtles, Crane, Deer, Pine, Rock and Bamboo, as well as designated areas for exercise and agriculture, ecozones, and scenic overlooks. Fragments of the "dragon" appear throughout the park, as in this "Bamboo Walk" which leads to a tranquil pond, where five "dragon-claws" thrust out of a mountain-outcrop and then transform into five trails. Korean animism is based on the belief that Hananim, the One Lord, has endowed mountains, rocks, and trees with part of his spirit. These "spirit-dwelling places" form Ulsan Park's natural and restored ecologies. |

||||||

Evocations of the KOREAN DRAGON appear throughout Ulsan Park. Huge "dragon claws" form major nodes, at park entrances and along the "Dragon Trail" and promenade. The claws emerge from the earth and incorporate functional elements, such as seating, paving, bridges, and planting, often manifested sculpturally or in bright colors. Other evocations of the "dragon"— flames, scales, ridge-crest, ventral plate— appear within the natural landscape and function as special features, or as part of the park's circulation system. |

||||||

DRAGON'S EYE-CLOUD GARDEN © Patricia Johanson 1996 Occupying the highest point of land, at the end of the Dragon Trail, the "dragon's eye" functions as a powerful, watchful symbol, looking toward the protective "Grandfather Mountain", and overlooking the city of Ulsan below. This is the place where the legendary Water Dragon and Celestial Dragon meet — the union of heaven and earth — as clouds are pulled down from the heavens into a large reflecting pool. A "Bat Pavilion" refers to the real bats that appear at sunset, just as red light is transforming the yellow and blue colors of the garden (the colors of the Celestial Dragon and the Blue Dragon) into orange and purple. |

||||||

"LIVING GATE" AND DRAGON TAIL FOUNTAIN © Patricia Johanson 1996 The "Living Gate" — part of a walled courtyard with a tranquil inner pool and pavilion — is composed of traditional Korean architectural elements such as bird-wing brackets, which support vegetation, perches, and nesting shelves. The "tail" of the dragon culminates in a huge civic fountain at the northeast entrance to the park. By following the blue, scale-patterned "tail" path uphill, past courtyards, restaurants, and Imax Theater, one arrives at the summit, where the "Dragon Trail" unfolds along the crest of the mountains. |

||||||

The DRAGON TRAIL follows the natural contours of mountain ridges. |

||||||